Carlo Mollino lived like a man unwilling to choose. Architect, designer, photographer, pilot, skier, racer, mountaineer, writer, playboy—he pursued each with equal fervor, collapsing the boundaries between life and art until the two became indistinguishable. Remembered as one of mid-century Italy’s most original creators, Mollino was less a practitioner of disciplines than a conjurer of worlds, each of his projects serving as a stage for his restless imagination.

Carlo Mollino lived like a man unwilling to choose. Architect, designer, photographer, pilot, skier, racer, mountaineer, writer, playboy—he pursued each with equal fervor, collapsing the boundaries between life and art until the two became indistinguishable. Remembered as one of mid-century Italy’s most original creators, Mollino was less a practitioner of disciplines than a conjurer of worlds, each of his projects serving as a stage for his restless imagination.

Born in Turin in 1905, Mollino studied architecture at the local university in Turin before working alongside his father, a respected engineer. Early commissions revealed both his talent and his refusal to obey convention. The interiors of Casa Miller (1936) and Casa Devalle (1938) were baroque dreamscapes: surreal, erotic, and utterly of his own idiom. By the 1940s and 1950s, Mollino’s portfolio had expanded to Alpine resorts, apartments, and auditoriums, each commission marked by daring forms and materials.

He treated design as theater. Chairs and tables became sculptural apparitions, one-of-a-kind creations that resisted serial production, their sinuous lines echoing the aerodynamics of the automobiles and aircraft he adored. His furniture was not meant to be neutral—it was meant to seduce. In 2005, one of his 1949 tables fetched $3.8 million at Christie’s, a testament to the enduring magnetism of his vision.

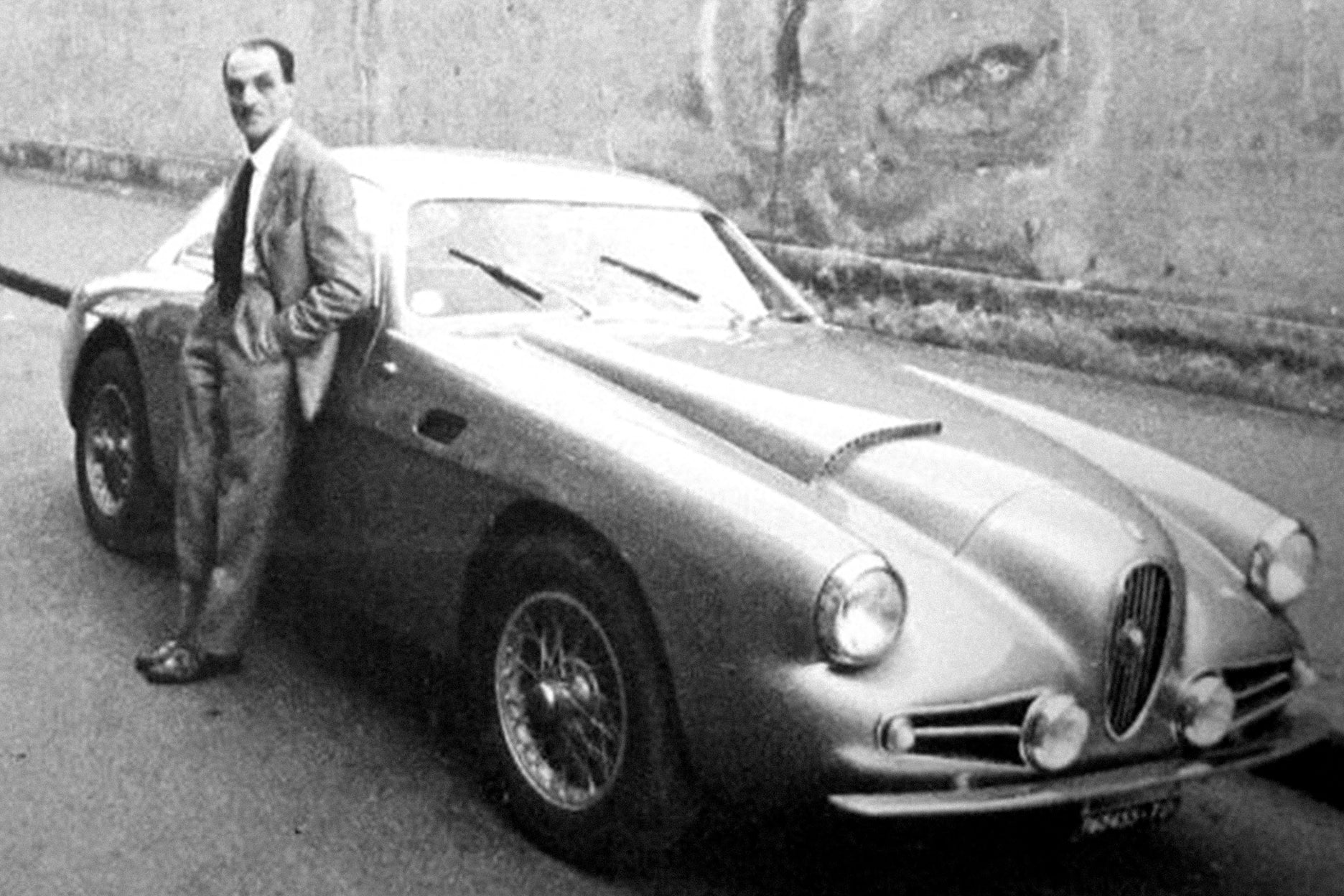

Mollino’s work in architecture reached its zenith with the RAI Auditorium in Turin (1951), where his low-slung armchairs invited both repose and spectacle. But it was the fantastical “Bisiluro,” the twin-fuselage racing car he designed for the 1955 Le Mans, that captured the full force of his obsessions. A metallic chimera recalling wartime aircraft, it lacked competitive performance but radiated surreal allure with its unique combination of sculpturality and speed.

Throughout his life, Mollino imbued the inanimate with intimacy. His photographs—particularly the thousands of erotic Polaroids discovered after his death in 1973—reveal a fascination with the female form, not as subject but as architecture: stylized, staged, and mythologized. His interiors, furnishings, and photographs alike carried a biomorphic sensuality, surfaces that seemed to breathe, colors that hinted at flesh, compositions whose reverie blurred reality.

For all his versatility, Mollino left behind remarkably little. Few of his buildings survive intact, and most of his designs were made in limited quantities for private commissions. Yet this scarcity only sharpens his aura. He remains a figure of Italian modernism and even moreso, a legend. An artisan of the surreal, a dreamer of speed and sex, Mollino designed as he lived—recklessly, passionately, and entirely on his own terms.

WRITTEN BY Andrew Pogany

#ARTs