In the aftermath of World War II, Tokyo was a city both broken and becoming, a restless metropolis swelling with migration, ambition, and an economy surging toward modernity. In the wake of World War II’s devastation, economic advancement was exploding, and buildings could not keep pace with society’s velocity of change.

In the aftermath of World War II, Tokyo was a city both broken and becoming, a restless metropolis swelling with migration, ambition, and an economy surging toward modernity. In the wake of World War II’s devastation, economic advancement was exploding, and buildings could not keep pace with society’s velocity of change.

Into this atmosphere stepped a radical group of four young architects who, in 1960, published a manifesto titled Metabolism: The Proposals for a New Urbanism. Among them was Kishō Kurokawa, a figure who would become both the voice and the face of the movement that sought to imagine architecture not as a fixed monument but as a living organism.

The name Metabolism was not a metaphor plucked from the air but a deliberate provocation. In its Japanese form, shinchintaisha (新陳代謝), the word referred not only to the biological cycle of renewal but also to the Buddhist-inflected notion of impermanence: the inevitability of growth, decay, and regeneration. Architecture, the Metabolists insisted, should reflect this natural law. Cities were to be designed as dynamic systems, structures that could evolve, expand, or shed their parts like the cells of a living body. It was a vision as utopian as it was urgent—a new promise for a society racing into the future.

Kurokawa’s role was distinctive. Where some members of the group, such as Kiyonori Kikutake, leaned toward vast theoretical schemes like floating Marine Cities, Kurokawa became the great translator of Metabolist ideals into built form. His concept of symbiosis—a philosophy of coexistence between opposites, between man and nature, tradition and modernity, permanence and impermanence—was central to his thinking. He thought of architecture not as pure futurism, nor as nostalgic pastiche, but as an ongoing negotiation between visible and invisible traditions: the visible being material form, the invisible being cultural values, like receptivity to time and change.

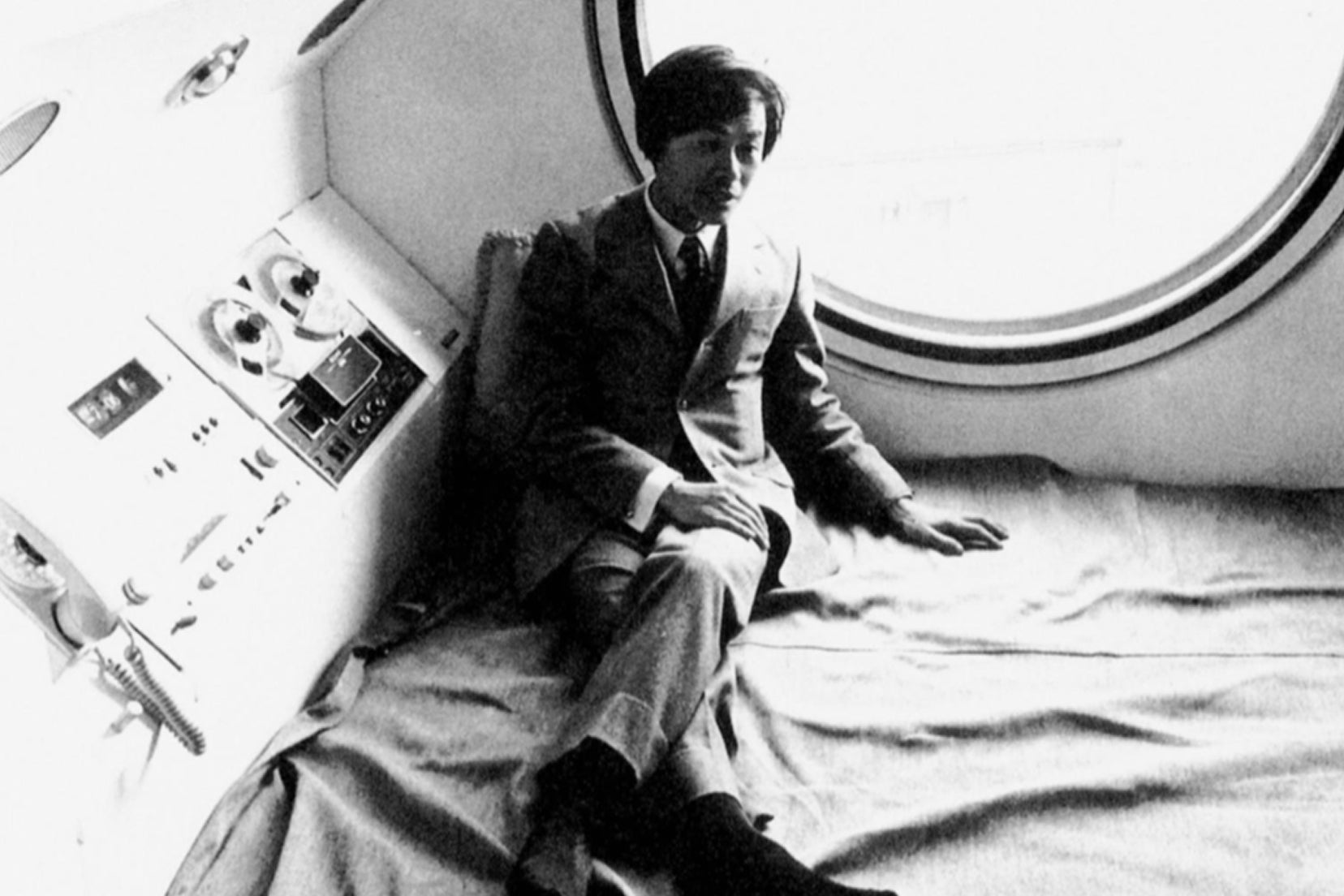

The clearest embodiment of this ethos was the Nakagin Capsule Tower, completed in Tokyo in 1972. Rising from two concrete cores, the tower’s prefabricated capsules were designed to be plugged in and could eventually be replaced, each a compact dwelling outfitted for the hypermodern salaryman. The building became an icon of modularity and a bold experiment in temporality, promising a future in which the city itself could be reconfigured with the ease of assembling machinery. Here was the Metabolist dream made tangible: permanence in the core, impermanence in the units, designed for an ever-evolving city. Yet the fate of the tower—long neglected, beset by decay, and ultimately dismantled in 2022—also revealed the challenge of translating utopia into sustainable practice. The idea was visionary, the execution fragile, its ambition colliding with economic, political, and logistical realities.

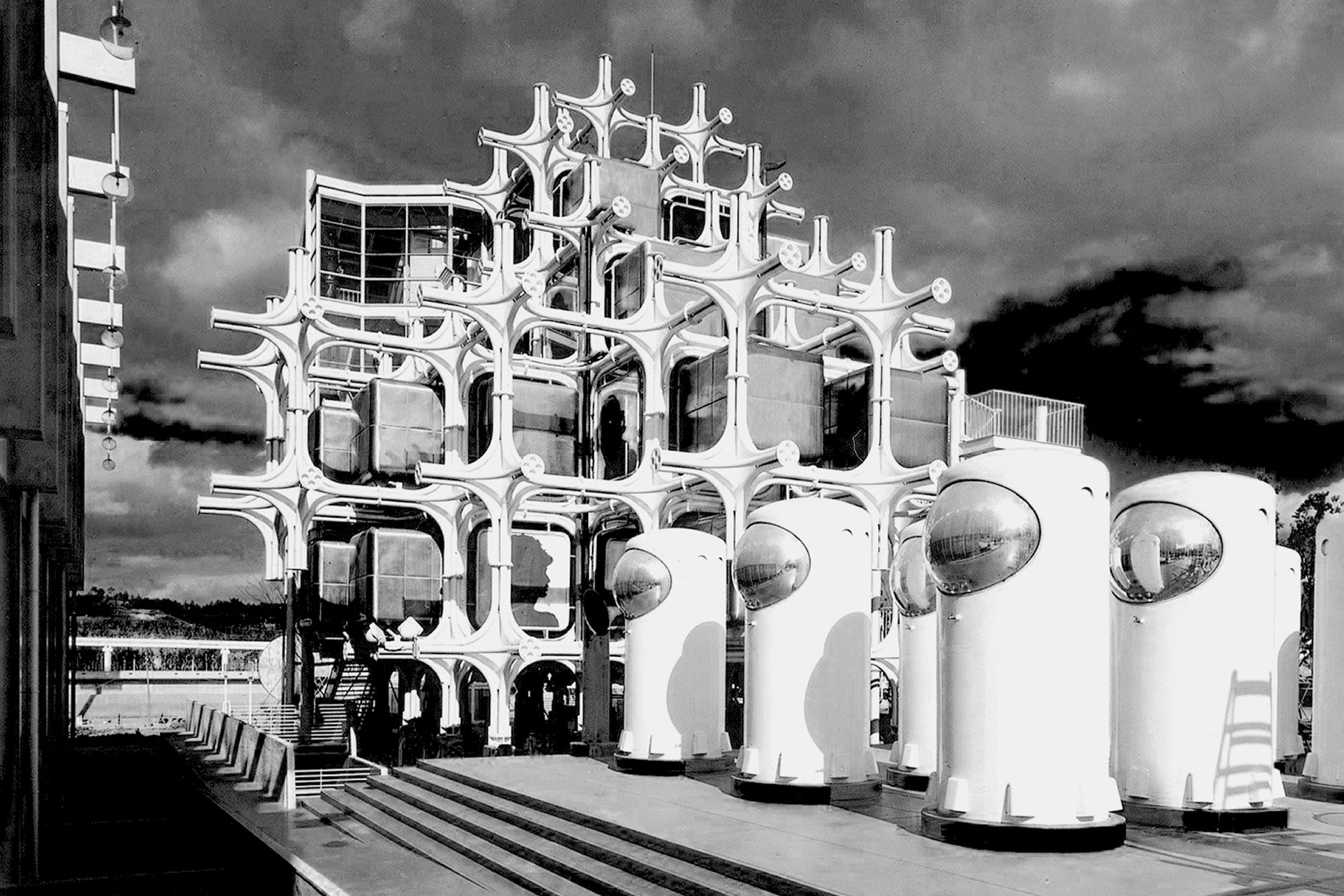

Still, the Tower was only part of the story. Kurokawa and his peers had first tested their ideas on the stage of Expo ‘70 in Osaka, where pavilions served as laboratories of prefabrication, modularity, and megastructure design. These experiments made clear that the Metabolists’ architecture resembled the growth of a tree: a trunk providing stability, supporting branches and leaves that could be renewed. The city, in their imagination, was not a grid of stone and steel but an organic system, a Bio-Tokyo that exchanged energy and resources with its environment. Even in projects that remained on paper, like Kurokawa’s Space City or Agricultural City, one senses the same insistence that the metropolis should be alive, adaptive, symbiotic.

Of course, such visions were expensive, and the laws of physics were often unforgiving. As the Sabukaru essay The Promised Tokyo notes, the Metabolists knew the impossibility of fully mobile cities. Their compromise was to separate what could move from what must remain fixed, creating massive frameworks into which replaceable units could be inserted. This idea of the megastructure—enduring scaffolds populated by disposable capsules—remains one of the most influential legacies of the movement.

By the late 1970s, however, the momentum of Metabolism had slowed. Economic shifts, maintenance failures, and changing architectural fashions relegated many of its grand proposals to the archives. Yet, in retrospect, their work feels prophetic. Today, as we face the demands of climate change, rapid urbanization, and resource scarcity, the Metabolists’ call for adaptable, modular, and renewable architecture seems less like a utopian dream than a necessary paradigm. Their belief that buildings should anticipate change rather than resist it resonates with contemporary ideas of lifecycle design, disassembly, and sustainable modularity.

Kurokawa himself continued to refine his philosophy of symbiosis, extending it beyond architecture into urbanism, politics, and even cultural theory. He remained convinced that architecture’s role was not only to house but to harmonize, to act as a living mediator between competing forces. If the Metabolists’ schemes were not always practical, they were deeply poetic—gestures toward a city that could be as fluid and regenerative as the people who inhabited it.

In the end, the Metabolist Movement was less about the permanence of its structures than the permanence of its ideas. Through Kurokawa’s voice, it articulated a vision of architecture as organism, as experiment, as a mirror of human society in flux. Their imagined Tokyo—part science fiction, part Buddhist parable—may never have been fully realized, but its spirit lingers in every attempt to design cities that can grow, adapt, and survive.

WRITTEN BY JMM

#ARTs