In the pantheon of artistic awakenings, few relationships are as hauntingly symbiotic as that between Arthur Rimbaud and Patti Smith, two poets separated by a century yet bound by a shared belief in the alchemy of language and its capacity to liberate consciousness.

In the pantheon of artistic awakenings, few relationships are as hauntingly symbiotic as that between Arthur Rimbaud and Patti Smith, two poets separated by a century yet bound by a shared belief in the alchemy of language and its capacity to liberate consciousness.

“A Season in Hell was the drug of my youth,” Smith has said. “Such is the exhilarating power of poetry.” Not out of mere admiration, but devotion—to a lifelong dialogue between a late-19th-century prodigy who redefined the limits of verse and a 20th-century punk priestess who transformed those same ideals into song.

Rimbaud, the enfant terrible of French letters, lived only briefly within the realm of literature, but set it ablaze. Born in 1854 in the Ardennes, he began writing verse as a teenager. His poems, first pastoral and then progressively anarchic, detonated the conventions of French poetry. In works like Le Bateau ivre (The Drunken Boat), he fused synesthesia, mysticism, and rebellion into a single, luminous current. “I is another,” he declared in a letter at seventeen, rejecting the self as fixed or knowable, insisting instead on the poet as a vessel, not author.

His relationship with the poet Paul Verlaine would only deepen his myth. Together they embodied an explosive union of passion and intellect, scandal and creation. Their affair, conducted in Paris and then in exile across Europe, inspired some of Rimbaud’s most incandescent work, but ended in violence when Verlaine, drunk and desolate, shot him in the wrist. By twenty-one, Rimbaud had renounced poetry altogether, leaving Parisian cafés for the deserts of Africa, where he traded in guns and coffee until his death at thirty-seven. He published no memoir, left no final statement—only the afterglow of verse that still feels like the future.

For the generations that followed, Rimbaud’s abandonment of art became as compelling as his creation of it. He was the prototype of the modern punk: the artist who refuses the system even at the cost of his own genius. His fingerprints can be found across Dadaism, Surrealism, and Modernism; his spirit flickers in the cut-up techniques of William Burroughs, the ecstatic visions of Allen Ginsberg, the lyrics of Bob Dylan and Jim Morrison. To read Rimbaud was to be initiated into a lineage of artistic insurrection, a secret society of those who saw poetry not as ornament but as a spiritual weapon.

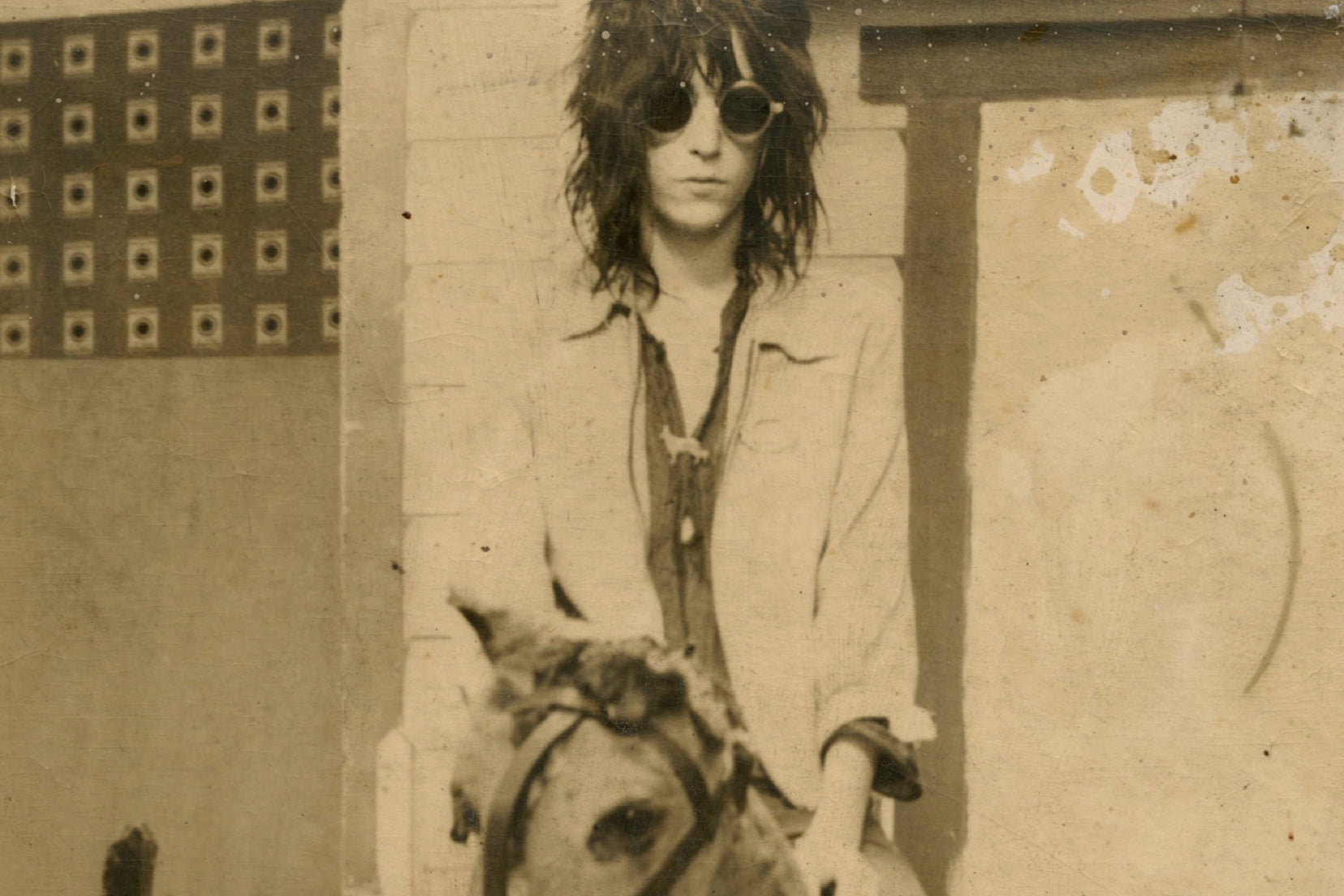

For Patti Smith, Rimbaud’s writings were scripture. Growing up in working-class New Jersey, she discovered Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell as a teenager and recognized in it the contours of her own hunger for art, freedom, and transcendence. His image, gaunt and defiant, became her talisman; she carried his photographs, visited his haunts, learned French to read him in his own tongue. “He was the brother I never had,” she said. When she moved to New York in the late ‘60s, Rimbaud came with her as a ghostly companion.

That communion found its full expression in Horses (1975), her debut album and one of rock’s most literary revolutions. Like Rimbaud’s verse, it was raw and visionary, fusing poetry and punk, the sacred and profane. The opening line—“Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”—could have been written by the young French poet himself. Smith’s performances at the infamous CBGB were séances of sorts, where she summoned the same fevered energy that once burned through The Drunken Boat. In her work, as in his, language was not merely a description but invocation.

Rimbaud’s influence on Smith went beyond aesthetics—it became a philosophy of being. Both saw the artist as a kind of clairvoyant, one who must undergo “a long, immense, and rational derangement of all the senses” to reach truth. Yet, where Rimbaud ultimately fled from art, Smith made the opposite choice: she stayed. Her devotion was redemptive, her rebellion enduring. In her books Just Kids (2010) and M Train (2015), she writes of Rimbaud not as a distant idol but as a constant companion, a mirror through which she measures her own artistic faith.

Through her, Rimbaud’s legacy found new voice. The ecstatic violence of his imagery, the moral audacity of his youth, his insistence on living at the edges. And through him, Smith inherited a lineage that stretches across time and discipline: from Verlaine’s absinthe-soaked salons to Dylan’s highways, from Ginsberg’s Howl to Morrison’s desert visions. They are all fragments of the same experiment, the same belief: that poetry can remake the world.

In the end, Rimbaud’s exile and Smith’s endurance complete each other: the poet who vanished into silence, and the singer who never stopped writing. Both sought transcendence through art and suffered for it, but where one turned from the fire, the other carried it forward. Their communion reminds us that poetry’s true power lies not in words alone, but in what they awaken—the courage to dream beyond convention, to engage in that grand and dangerous act of faith known as creation.

Such, indeed, is the exhilarating power of poetry.

WRITTEN BY JMM

#ARTs