A man who transformed racing into both an art and a ruthless obsession, Enzo Ferrari lived for speed and spectacle. He was a driver who preferred command to competition, a manager who styled himself “an agitator of men,” and a showman who turned the prancing horse into an international emblem of power, danger, and desire.

A man who transformed racing into both an art and a ruthless obsession, Enzo Ferrari lived for speed and spectacle. He was a driver who preferred command to competition, a manager who styled himself “an agitator of men,” and a showman who turned the prancing horse into an international emblem of power, danger, and desire.

Born in Modena in 1898, Ferrari’s youth was shaped by loss and upheaval. The deaths of his father and brother in 1916, his own near-fatal brush with the influenza pandemic of 1918, and the collapse of the family business left him with little but his determination.

After serving with the Italian Army, he found his way to Alfa Romeo, first as a driver, then as a strategist, where his real talent emerged: orchestrating men and machines into something greater than either could achieve alone. By 1929, he had founded Scuderia Ferrari, assembling champions like Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari under a banner soon to bear the Cavallino Rampante—borrowed from the fallen aviator Francesco Baracca, set against the yellow of Modena.

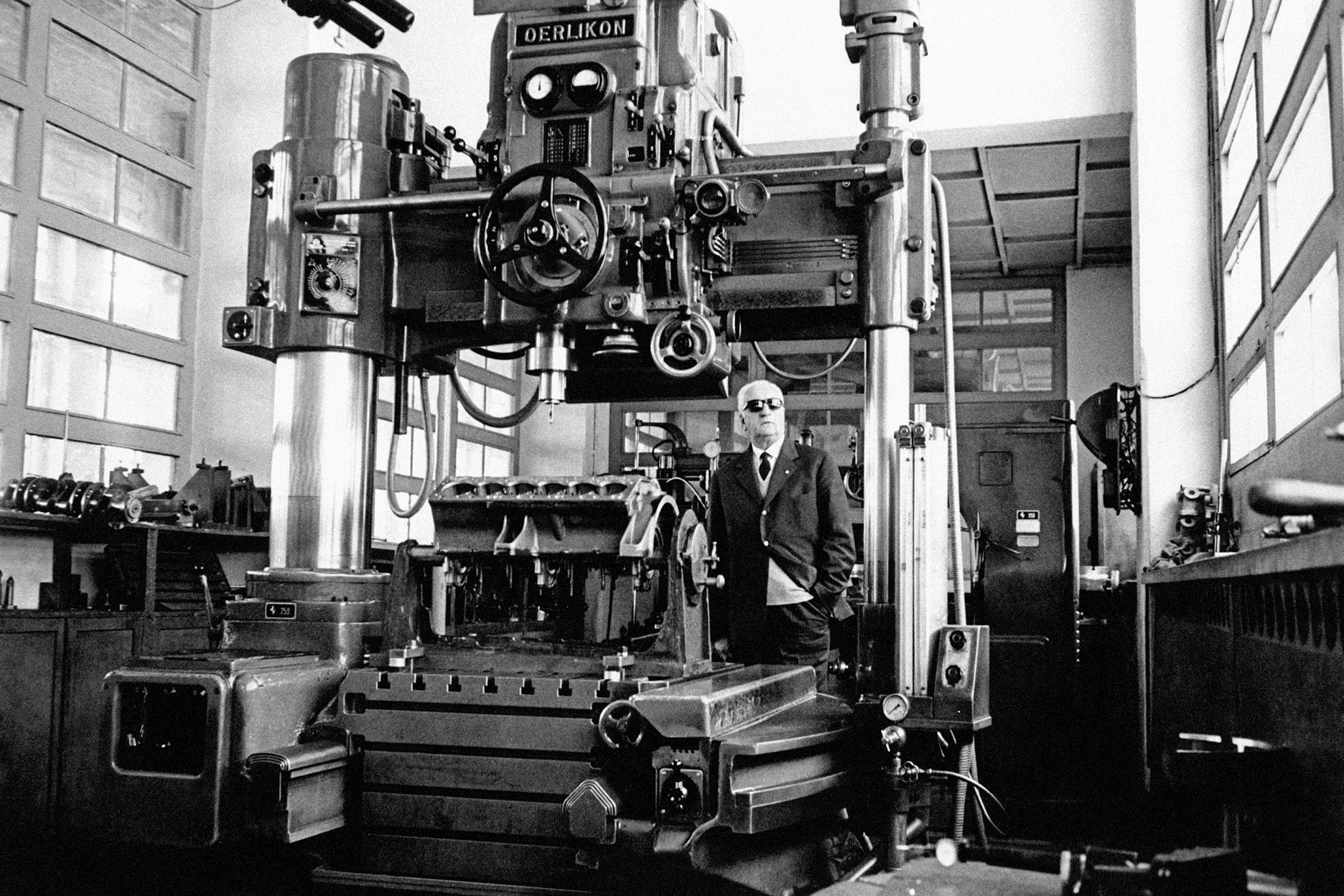

Racing defined him, but it was not enough. In 1947, with Ferrari S.p.A., he launched cars of his own, financing his teams by building machines that seduced Europe’s aristocracy, Hollywood stars, and Riviera playboys. These were not just automobiles but declarations: extravagant, sculptural, embodiments of arrival and allure. Yet behind the glamour lay a man utterly consumed by competition. To him, the road to victory demanded sacrifice—sometimes of others more than himself.

Ferrari’s management style was famously ruthless. He pitted drivers against one another, stoked rivalries, and cultivated pressure like an accelerant. The results were undeniable—six consecutive victories at Le Mans from 1960 to 1965—but so was the toll. The list of dead stretched long (Collins, Castellotti, Musso, von Trips, Bandini), with the Vatican’s own newspaper likening Ferrari to Saturn devouring his sons. The most infamous disaster came at the 1957 Mille Miglia, when Alfonso de Portago’s crash killed both driver and spectators, igniting a trial that charged Ferrari himself with manslaughter before his eventual acquittal.

Yet the controversies never slowed him. If anything, they sharpened his legend. Ferrari embodied the paradox of his own machines: brutal and beautiful, precise and unpredictable, vessels of ecstasy and risk. He was a salesman who knew how to seduce with style, but above all, he remained a man obsessed with winning. “Ferrari’s only interest was victory,” said Niki Lauda, who drove for him and knew both his iron ego and his rare flashes of warmth. “He was absolutely focused in a brutal way. But in the end, he was Italian, and he had a heart.”

Enzo Ferrari died in Modena on August 14, 1988 at 90 years old. Former Ferrari F1 team principal (1977-1988) Marco Piccinini was one of just a handful of people who attended Enzo's funeral ceremony. "In private, he was humble,” said Piccinini.

“He didn't take himself overly seriously and could see the humor in the situation. What he did take very seriously was the factory, the work and the people who worked for him. Enzo Ferrari didn't need to play up to a perception. You don't need to pose like Ferrari when you areFerrari."

WRITTEN BY Andrew Pogany

#