Jacques Marie Mage is committed to working in support of wildlife, wild places, and the Indigenous peoples who are the original stewards of the landscapes we inhabit today. Through years of building a deep partnership that combines donations, creative collaborations, and awareness-building, JMM has become the most significant supporter of Sage to Saddle and is proud to watch the organization expand its critical efforts.

Jacques Marie Mage is committed to working in support of wildlife, wild places, and the Indigenous peoples who are the original stewards of the landscapes we inhabit today. Through years of building a deep partnership that combines donations, creative collaborations, and awareness-building, JMM has become the most significant supporter of Sage to Saddle and is proud to watch the organization expand its critical efforts.

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota is notorious for its numbers. At 2.1 million acres, it’s one of the largest reservations in the United States. Only 84,000 of those acres are suitable for agriculture. Of the 19,157 residents, 48.2% live below the poverty line. Oglala Lakota County has the lowest per capita income in the nation, not to mention ranking last regarding quality and length of life. The unemployment rate on Pine Ridge is about 90%. The school drop-out rate, 70%. And with a teen suicide rate 150% higher than the national average, the hard winters are colloquially known as “suicide season.” It’s a largely forgotten place in the heart of America, less than 100 miles from the bustle and sheen of Mount Rushmore.

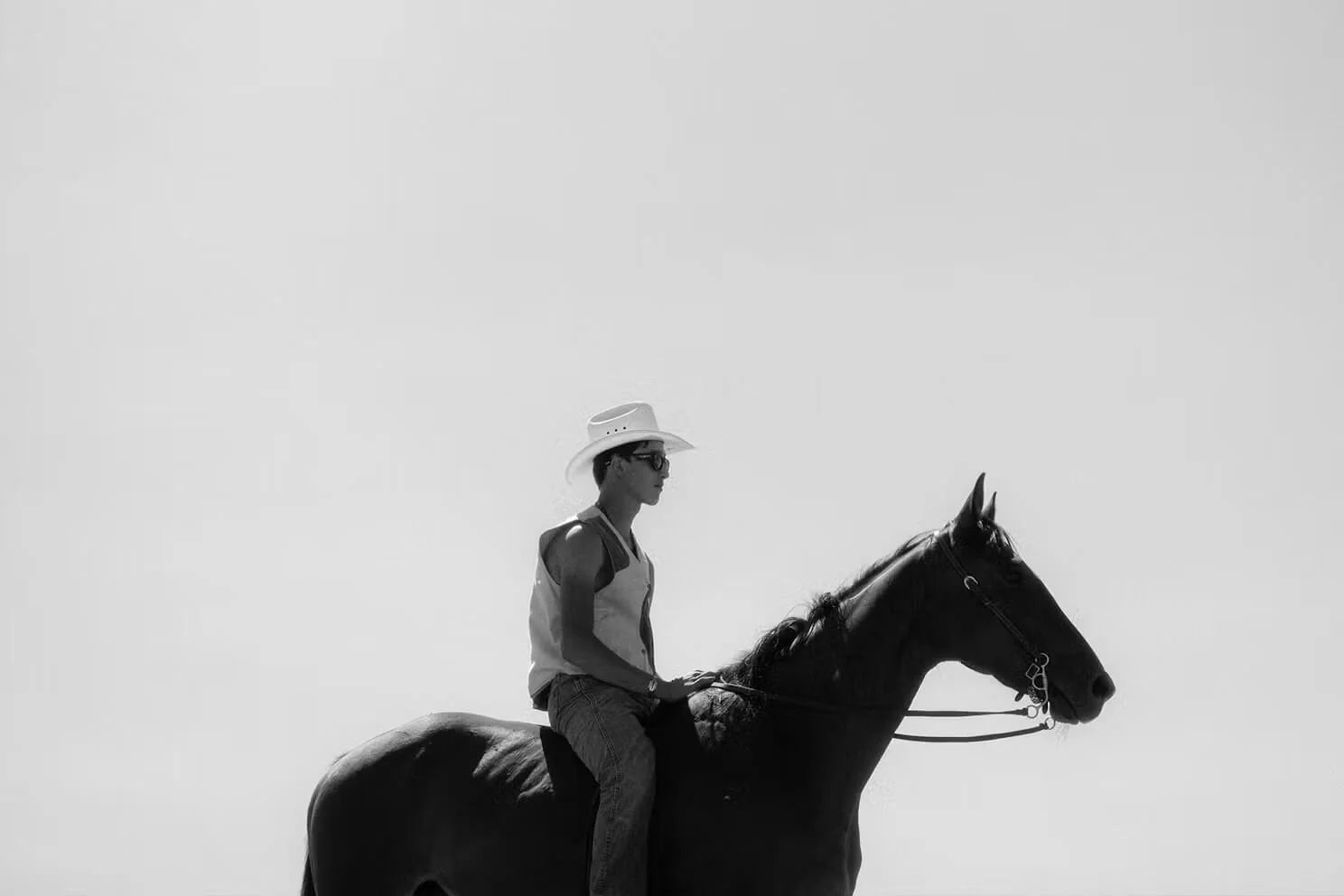

Enter Sage to Saddle, the 501(c)(3) nonprofit founded by Nate Bressler that, at face value, teaches horsemanship responsibilities and leadership skills to kids on Pine Ridge. But it’s much more than that: In the unforgiving grip of the prairie, Sage to Saddle is a lifebuoy. Bressler, along with Nonprofit Coordinator Angie Smith and world-renowned horse racing champ Stan Brewer, provides at-risk kids a safe space, fun activities and a range of new experiences—on and off the Reservation.

For its first four years, Sage was largely seasonal; there were no indoor heated riding facilities for winter use. But, thanks to donations, help from the community and its leaders, and an astounding amount of grit and determination, this past winter was their first with a working arena on a Reservation that is the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined. This offers kids and their parents something to see them through the hardest season of the year, in one of the hardest places on earth.

We caught up with Nate Bressler to discuss this exciting new development, the importance of responsibility and sense of self, and what’s next for Sage to Saddle.

J.M.M.:What have you been up to since we last spoke?

NB:January [of 2023] was the first month we were actually in the arena—we purchased the arena last year—so we were able to get in there and work with some of the local high schools and their afterschool programs. So we got up to about 20 kids a day getting in there, you know, and it’d be different kids. But we started getting them in there late January, and word spread like wildfire across the Reservation. And we kept kids coming in there until May, so we got a good few months in there for our first year.

We got a lot more physical, just tribal support from everybody around—the elders saw me coming out for four years now, I’m on my fifth summer, and they knew what I was doing. So that really helped Sage to Saddle in how it was viewed on the Reservation, because it’s run by a white man, even though Stan [Brewer] is my partner and is Lakota. I started Sage on August 4th of 2018, and now it’s probably ten years ahead of where I thought it could’ve been, and I’ve been able to dedicate myself fully to it.

Going into the arena [during winter months] was a big advantage for us. We bought a 15-passenger van in February because there’s always a bus shortage—they’ve got [Chevy] Suburbans but they’re always broken down, the buses don’t have heat, they don’t have air conditioning. So we bought the van to move the kids around.

J.M.M.:You guys started your own ride this year?

NB:Yeah, the Sobriety Ride. There have been sobriety rides for years, but it’s less about making sure the kids are sober for three days; it’s more about thinking about your friends and family and people who’ve died due to addiction. It’s about the community acknowledging the tragedies that have happened with addiction. Because the addiction rate [on Pine Ridge] is way higher than the national average.

So we do our Sobriety Ride in the first week of August, and we actually got to kick off the big fair weekend—you know, we have one big fair, the pow wow, rodeo, everything—it’s the Lakota Nation’s fair, and we rode in with 75 kids our first year, and we had more kids show up for that group ride than any other.

J.M.M.:In terms of group rides, what sets Sage apart?

NB:With Sage to Saddle, I go on every ride. The kids get to actually ride with the people who put it on, and we’re all young and fun and tell jokes and can kid around with ’em. So when we get back to camp, we’ve already got that bond from going 30 miles on horses during the day, and already had all those laughs. So then if we wanna talk about things more seriously or ask for their involvement, we can get a lot more out of them. You know, it’s the first group ride where the people who are putting it on are directly connected to the ride. So that’s had a lot of impact out there.

And we’re probably gonna do two next summer, we’re just gonna keep growing with these group rides. Like I said: 75 kids the first year, and I bet next year we’ll have over a hundred, and we’ll grow every year. It’s something that we’re very proud of.

J.M.M.:Let’s talk about the arena.

NB:Now that we’re running in the arena, we’ve got 17 kids working for us, off and on. But we’re now the biggest employer on the Reservation that’s non-governmental.

J.M.M.:Wow.

NB:Yeah. We have more kids, we pay ’em $13 an hour, we pay some of the older ones a little bit more, especially ones who pay for gas. But they’re making almost twice the minimum wage… You know, the unemployment rate out there is staggering, 75% unemployment. There’s no industry or anything like that. There’s no job opportunities besides government jobs—working for the hospital, working for the schools, driving a plow. Besides the one grocery store, we are the biggest employers out there.

That means a lot to us: we’re not just hiring locals, we’re hiring kids straight outta high school or in their early twenties who’ve already come through our program. A lot of these kids are very quiet the first week when they’re working for us, but we really develop their leadership skills, encourage them to get their driver’s license—well, not even encourage; we make damn sure they do—opening up bank accounts, and of course all the things that come with a job like that, being on time. So we get to make an economic impact out there that I didn’t even realize or anticipate at the beginning.

J.M.M.:How has the scope changed since Sage’s inception?

NB:Well, now we’ve got parents who come along and are more involved. So when we do a lot of stuff in the arena, we encourage the parents to come so they can be inspired by seeing what their kids are doing.

J.M.M.:And a far-reaching benefit, too, is that these kids will themselves be adults someday, and they’ll have this experience that their parents didn’t have.

NB:Exactly. That’s the whole thing: trying to break that cycle. Everything is cyclical out there. This is one of those things that maybe could actually help give people reasons to keep out of trouble and be more involved and to see there are people out there who are behind them.

I’m hoping that the ripple effect of all this is multi-generational. And, of course, as we go along, these kids become wranglers for us and then they go on and we help them find jobs off the Rez. Unfortunately, as much as we’d wanna keep these kids on the Rez, there’s no opportunity there. And my friends [on Pine Ridge], from day one, I was like, What are your goals for this? And they all said, you know, to get these kids out of here and never come back. Which was really hard for me to stomach, at first. But the more people I spoke to and the more I saw, there’s nothing out there but addiction and crime and murder and suicide and no work opportunities at all. So why would you want to keep a kid around for that?

J.M.M.:Tell me about your first winter in the arena. How’d you feel?

NB:I thought I was gonna be crying every day this winter because we finally had kids in there. But once it was going full swing, it was already happening and I didn’t have time to, like, emotionally draw into it and realize all this hard work coming to fruition. It was just like, now we got the next problem and the next thing to get over and the next hurdle, and they’re really responding to this, all right, let’s not slow that down, let’s start talking to more school boards and more superintendents.

J.M.M.:What’s next?

NB:Ultimately, in the next couple years, we’re gonna build a satellite arena that’s gonna be not quite as big. But it’ll be on the other side of the Reservation, so we can really cover all the kids. There are seven Lakota Nations within South Dakota. So the idea is—and has been from day one—to build at least ten of these. I think we’ll have another arena on Pine Ridge in the next year or two, and hopefully we’ll have five within the next ten years. You can put that on paper, and I’ll stick to it.